Joseph Lyman Silsbee and the Roots of the CNY Arts and Crafts Movement

- artscraftscny

- Mar 20, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 21, 2023

by Samuel Gruber / ACSCNY

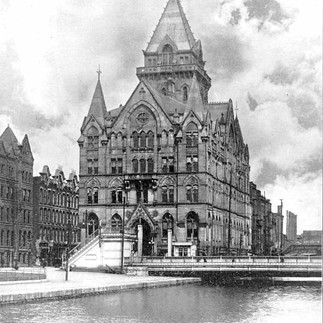

Anyone from Syracuse is familiar with Joseph Lyman Silsbee's most famous building, the former Syracuse Savings Bank built on the east side of Clinton Square in 1875. It was his first big commission and was a smashing success. Silsbee had moved to Syracuse just two years before from Boston. He came to run the office of Horatio Nelson White while White traveled in Europe, and also to teach (unpaid) at the still-new Syracuse University. Just two years later he was engaged to Anna Baldwin Sedgwick, daughter of one of the city's favorite sons, and he'd won the competition for the Syracuse Saving Bank to be built right across the Erie Canal from the Onondaga County Savings Bank designed by H. N. White. White had built two other noteworthy building on Clinton Square, the Wieting Opera House and the County Courthouse (both gone). In the 1870s, Clinton Square was the center of action in the city.

Silsbee was born in Salem, MA in 1848 he came from a distinguished New England family. His father was a Unitarian minister (as was the father of Frank Furness). In 1863 he entered Phillips Exeter Academy, and then Harvard College (the family school) in 1865. Silsbee entered the new architectural program at MIT in 1869. It had been established by William Robert Ware the previous year as the nation’s first academic architectural program. Over the next two decades many leading American architects would train at MIT, including several who would make their names in Syracuse, such as Alfred Taylor, Ward Wellington Ward and Edward Bonta. Ware had worked in the offices of Richard Morris Hunt, alongside future "starchitects" Frank Furness, Henry Van Brunt, Charles Gambrel, and George B. Post, so he was well connected and graduates from MIT were able to find positions with many of the leading architectural firms in 19th-century America.

Ware's approach to architecture was different from that of the Ecole des Beaux-arts in Paris. He had a broad and flexible curriculum and was not insistent on the primacy of classicism. He mixed design and engineering and encouraged originality in conception, especially for the many new types of buildings that were being required in the period of late 19th-century industrial transformation of the country. We don't know exactly what Silsbee studied at MIT, but in 1870 he left before graduating and began work for Ware and Van Brunt, most likely on the Harvard Memorial Hall then in its final design stage of design.

In his important 1981 study of the early work of Silsbee, Donald Pulfer wrote that “we can be certain that whatever work Silsbee was doing, he was being trained in the most popular style in Boston at that time, the polychromatic High Victorian Gothic. Silsbee must surely have been exposed to the writings of John Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc. Ware's partner, Henry Van Brunt, was then in the process of translating the latter’s Discourses.”

In Pulfer’s words:

“In the 1870s Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc were the two poles of progressive architectural theory: from Ruskin came the ideal of morality and architecture and a picturesque, painterly vision; From Viollet-le-Duc came a structural rationalism with its apotheosis of the French gothic cathedral.... the high Victorian Gothic was eclectic and not archaeological like its earlier ecclesiastical phase. It emphasized truth of expression, honesty, and materials, in a rational approach to architectural problem solving. the Victorian Gothic movement was so successful and gave so much promise of becoming a truly independent American architecture, conditioned by this country's unique requirements and resources, that some critics mourned its passing decades after the arrival of the Richardsonian Romanesque and the American Queen Anne.”

Before coming to Syracuse, Silsbee also spent time working for William Ralph Emerson. From Ware and Van Brunt he certainly learned about large architectural projects - especially if he worked on Harvard's Memorial Hall. Emerson at the time was mostly working on houses albeit often very grand ones. Emerson worked in what we now call the “stick style,” and was one of the first to practice what became known as the “shingle style.” It's possible that the drawing method of Silsbee that Wright remarked upon in his autobiography was developed working with Emerson. Emerson stressed the value of sketching from nature, and he, like Silsbee, preferred a broad lead pencil as his primary drafting tool. Wright says he learned about houses from Silsbee, and Silsbee probably learned from Emerson.

So, in 1873 Silsbee brought to Syracuse education and experience in two contemporary trends of building – the High Victorian Gothic, influence by Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc (and others), and the new shingle style which competed together with the more ornate Queen Anne style shaped American residential architecture for a generation. Both styles lay the foundation for the American Arts & Arts Movement on the East Coast and the Midwest.

The Syracuse Savings Bank had begun to assemble a parcel in 1871 to expand the site of their existing building. They put together a building committee consisting of E.W. Leavenworth, the bank president, and four bank trustees and held a competition for the design of the new building

According to newspaper accounts of the time (reported by Donald Pulfer), “the committee devoted much of its time to obtaining a general idea to guide them in adopting a plan - taking the best points of various edifices and consolidating them;” “The committee was influenced in selecting the material in the style of architecture through their admiration for the city and county buildings of New Haven CT, and a large hotel than recently constructed by Charles Francis Adams near the southeast corner of the Boston Common.”

Pulfer points out that the competition was probably a private one. There was no announcement. One of the firms which participated was Cummings and Sears, which had designed the hotel in Boston that the committee admired. Archimedes Russell, Silsbee’s contemporary in Syracuse and also a colleague at Syracuse University, submitted a design. George Hawthorne and Frederick Mary of New York City also submitted designs, and the only design that has survived is by Andrew J. Warner and James G. Cutler of Rochester. Warner had designed the old Buffalo City Hall in a heavy Gothic style and in 1870 he built Rochester’s first fire-proof structure, the Powers building.

The City Hall in New Haven was one of the first polychromatic Italian Gothic buildings in the country. Knowing this we can certainly see some of the impetus for Silsbee's new design. Seeing Silsbee's design in the context of all these other architects and their submissions informs us that while his building was extremely creative in its massing and detailing, the choice of style was not really his. He was conforming to the desires and expectations of the bank and its building committee. Perhaps the proximity of the bank building to the canal suggested the Venetian style, but it is hard to say because the elements of Venetian architecture as transmitted by Ruskin had percolated through the architectural community by the 1870s.

A newspaper article on February 25, 1875, indicated that Russell’s design was favored, but the cost of his project was higher than that submitted by Silsbee. Significantly, the newspaper chose the two local artists the two local architect to single out for praise.

Over the years the Syracuse Savings Banks has won praise and dismissal from architectural critics. When built it was the tallest structure in the city and first and foremost is should be celebrated a urban landmark. It defines and holds its place masterfully. The building has always been popular with the public. It is great to look at from almost every angle and in every kind of weather. Having the space of Clinton Square allows the yellow stone to glow in the afternoon and sunset. The building combines the practicality of a bank and office building with the fantasy of a fairy castle. It can stand alone and center stage, but also play the part of city backdrop to perfection (as it does for the many festivals now held at Clinton Square).

This was Silsbee’s first big commission and launched a successful career which took him from Syracuse to Buffalo and then to Chicago. The influence of the building remained strong in the Arts and Crafts movement, and even in the era of Deco-Gothic of the 1920s. We can even imagine that the architects of the Niagara Mohawk Building had Silsbee’s Syracuse Savings Building in their sights – wanting to create a dazzling commercial landmark of similar stature.

(first posted on Facebook January 2022)

Comments